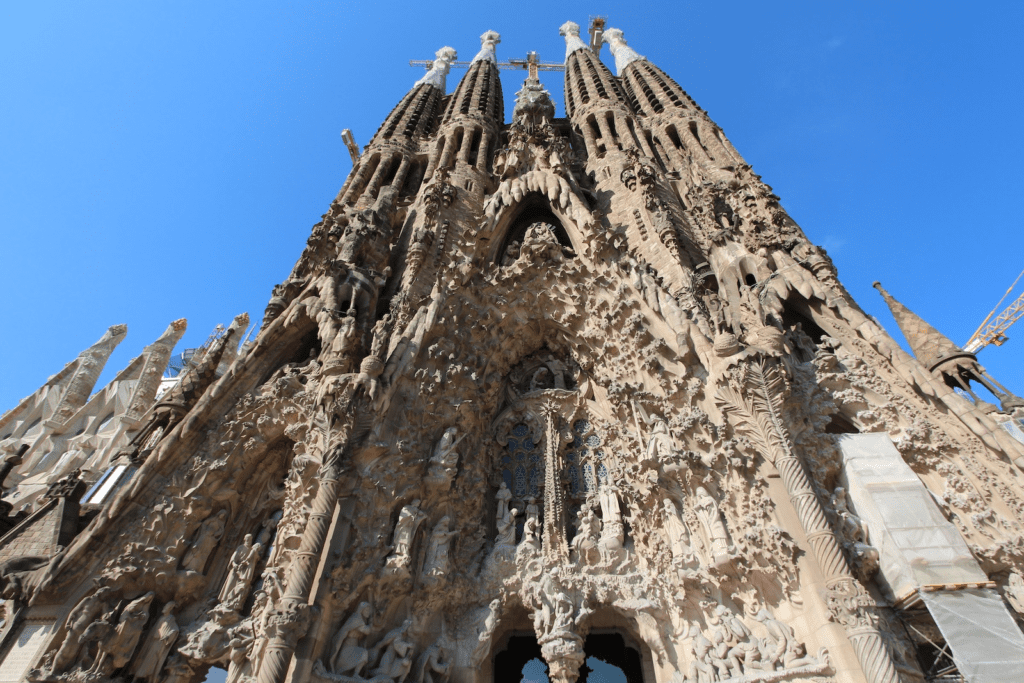

The Basilica of the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, Spain, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that has been under construction for over 100 years, earning it the reputation of a “building that will never be completed.”

However, it has recently been announced that the Chapel of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary will be inaugurated in 2025, and the 172.5-meter-tall main tower, the Tower of Jesus Christ, will be inaugurated in 2026, marking 100 years since Gaudi’s death. This news has generated significant excitement. To commemorate this historic development, we present the following article about the Sagrada Familia, translated and reprinted from Parametric-architecture.com.

A Review of Antonio Gaud’s Architecture: His Structural Engineering

Antonio Gaudí’s works invite each viewer to interpret them in their own way. Some of his works are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site “The Works of Antoni Gaudi.” The Sagrada Familia and Park Güell are landmarks for Barcelona’s local residents and are highly valued by the local government.

The unfinished state of the Sagrada Familia is remarkable. His architecture attracts many tourists, and architects and architecture students often study its composition and form.

I’ll explore his individual works in more detail in separate articles, but here I’ll take a look at an aspect that is often not considered: his structural engineering, or better yet, the philosophy behind his architecture and engineering.

Sagrada Familia Hidden Thoughts under Gaud’s Eyes

However, in this article, I aim to gain a deeper understanding of Antonio Gaudí as a person, as well as Gaudí the artist and architect. I hope to uncover and share the hidden thoughts that underlie his work, allowing readers to appreciate and come closer to understanding his creations.

Jeremy Law wrote this in his book titled “Antonio Gaudí,” published in 2009:

“We have to take into account the various factors that influenced his thinking, such as his family environment, childhood, place of birth and school, friends and relationships, and the countries in which he lived in Catalonia and Spain.

Why do we need to go to such lengths to understand Gaudi, including the history of what happened? The biggest reason for this is that it is difficult to understand Gaudi as simply a product of the era in which he lived.

In some ways, the Sagrada Familia may be similar to other large-scale productions undertaken in Europe at the time. For example, we can think of the works and philosophy of Le Corbusier, who is said to have admired Gaudi. However, Gaudí’s formal language and working process were completely different from those of his peers.

Comillas, a Catalan town near Bilbao, is home to El Capricho and Gaudi’s villa. In the courtyard, there is a statue of Gaudi installed in his honor.

In fact, there are very few bronze statues or photographs of Gaudi, and this bronze statue of Gaudi sitting and contemplating is a valuable piece that gives us a glimpse of what he looked like. Behind the façade of the formal structure that he envisioned, one can only imagine what the statue of Gaudi is thinking while looking at his own work. And it is only by observing Gaudi and thinking about him in this way that we can approach and understand his works.”

Gaudí’s family has been coppersmiths for over five generations

Gaudí’s family had been coppersmiths for over five generations, producing vats for distilling alcohol from grapes grown in the Camp de Tarragona. Gaudí himself admitted that he was greatly influenced by the curved form of the tub, which was made by hammering copper plates. He is said to have learned from the curved form of this copper vat that he could visualize his works in space, rather than projecting them geometrically onto a flat surface.

“This vision of colorful, shiny, soft metal-like, deformable, sculptural, vibrant forms, inspired by his childhood and his father’s workplace, became a constant element in his architectural practice.” Gaudí was also a shy child and spent many summers at his father’s country home, probably escaping the ongoing civil war in Spain.

The Influence of Nature on Gaud’s Personality and Artistry

Other events also played a role in shaping Gaudí’s personality and artistry. Law continues: “Gaudí’s ability to observe was also related to his childhood struggles with rheumatic fever. Often too sick to play with other children, Gaudí spent much of his time observing nature. He realized that there are countless shapes in the world, some very suitable for structures and others ideal for decoration. His keen intelligence allowed him to understand that each person has a unique form.”

Gaudí’s deep interest in nature profoundly influenced his work. In a sense, his architecture can be seen as a form of biomimicry, where he sought to incorporate and utilize the superior properties of the functions and structures found in living organisms and plants.

Gaudí was deeply concerned with the nature and essence of individual architectural elements. He became a master of his profession, meticulously understanding every detail of his work. Before construction, Gaudí conducted experiments to see how various components reacted to external forces, such as weight. His innovative approach involved using minimal traditional design tools like compasses and structural components like buttresses, allowing him to work freely and creatively, even improvising when necessary.

preferred 3D models to flat Euclidean geometry

Furthermore, Gaudí preferred using 3D models over studying flat Euclidean geometry. He constantly sought out and derived new forms from nature to deeply understand its complexity. Among his interests in natural forms, there were certain shapes he particularly focused on.

Let me explain this using Law’s words: “Gaudí noticed that in nature, we often observe curved surfaces that appear distorted—surfaces composed entirely of straight lines. In each case, the fibers remain straight, but when they twist or distort, they create what are known as ruled, warped surfaces. These curved surfaces began to be studied geometrically toward the end of the 18th century and were given complex names (primarily by Gaspard Monge): helicoid, hyperbolic paraboloid, conoid. These forms are relatively straightforward to create.”

As a result, Gaudí began to concentrate more on these particular forms and shapes within their context, considering available materials and local architectural traditions such as “lasillas” stone masonry. He observed that in Catalonia, slender bricks are laid to expose only their widest faces, typically forming surfaces one or two layers thick. These techniques are used for floors, partitions, walls, and even vaults within architectural spaces.

“He revolutionized traditional geometry by substituting cubes, spheres, and prisms with hyperboloids, helicoids, and conoids, embellishing them with natural elements like flowers, water features, and rocks. This approach extended to the construction of ‘voltes de maó de pla’ in Catalan, characterized by their curved surfaces.”

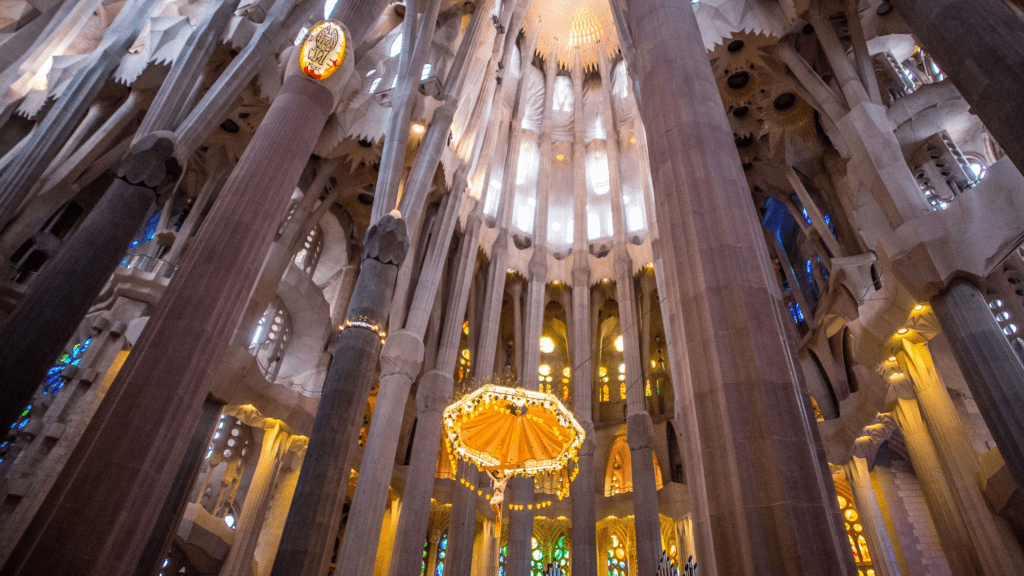

“He transformed the very essence of architectural geometry, fundamentally altering the landscape of art. Such forms are evident across his oeuvre, from the interiors of the Sagrada Familia to the entrance of Colonia Güell and the upper floors of La Pedrera. These groundbreaking works, characterized by sculptural architecture resembling lava and flowing fabric, embody the intricate beauty of the natural world.”

To conceive and construct such a building, Gaudí “did not even make use of the inventions of modern architecture, such as new materials like reinforced concrete and large steel structures. While these materials allow for imagining new forms, creating something innovative using traditional techniques is nothing short of genius.”

Gaudí had the ability to achieve precision and understood his techniques down to the smallest detail. His parabolas and hyperboloids played crucial roles in determining the vast sloping columns, vaults, and other structures. To achieve both absolute stability and a slender, elegant appearance, Gaudí designed all branching columns as double helicoidal twists. These were designed using ratios like 1-to-1/2, 1-to-2/3, 1-to-3/4, based on a simple ratio derived from one-twelfth of the largest dimension. For instance, dividing the total length of the temple (90 meters) by 12 resulted in segments of 7.5 meters each.

However, Gaudí’s works would not have captivated so many people without their beautiful and colorful decorations. Nevertheless, Gaudí himself believed that these decorative elements, which were similarly inspired by nature, were attached to and subordinated to the structural components.

Indeed, Gaudí’s concept of transforming a Gothic cathedral, as seen in the Sagrada Familia, might have been perceived very differently without its rich natural decoration. However, regardless of whether Gaudí placed more emphasis on the structural or decorative elements, his works tended to integrate the two seamlessly.

In an online blog called Gaudi All Gaudi, the author writes: “Gaudí was impressed by the vaulted ceilings of Catalonia, which skillfully used Roman bricks, the simplest finishing material of the time. Gaudí’s thorough mastery of geometry and his understanding of generatrices, influenced by this, inspired him to place ceramic tiles along the axis. The colors of the ceramic, combined with the green and golden glass in the joint openings, created a floral effect that had never before been seen in a cathedral. This resulted in the creation of a vault that looks like this.”

And Law concludes this way: “Their organic shapes and patterns offered not only structural possibilities but also countless decorative features. However, Gaudí’s works are replete with elements to unravel and ponder over; they are sophisticated reflections of the natural world that retain value even in an increasingly urbanized environment. No preparation is needed, just the awe and wonder akin to standing before the Grand Canyon.”

Must Read: UTILIZE THE “CREATIVE ARCHIVE” WHAT CLASSES DID RYUICHI SAKAMOTO TAKE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS?