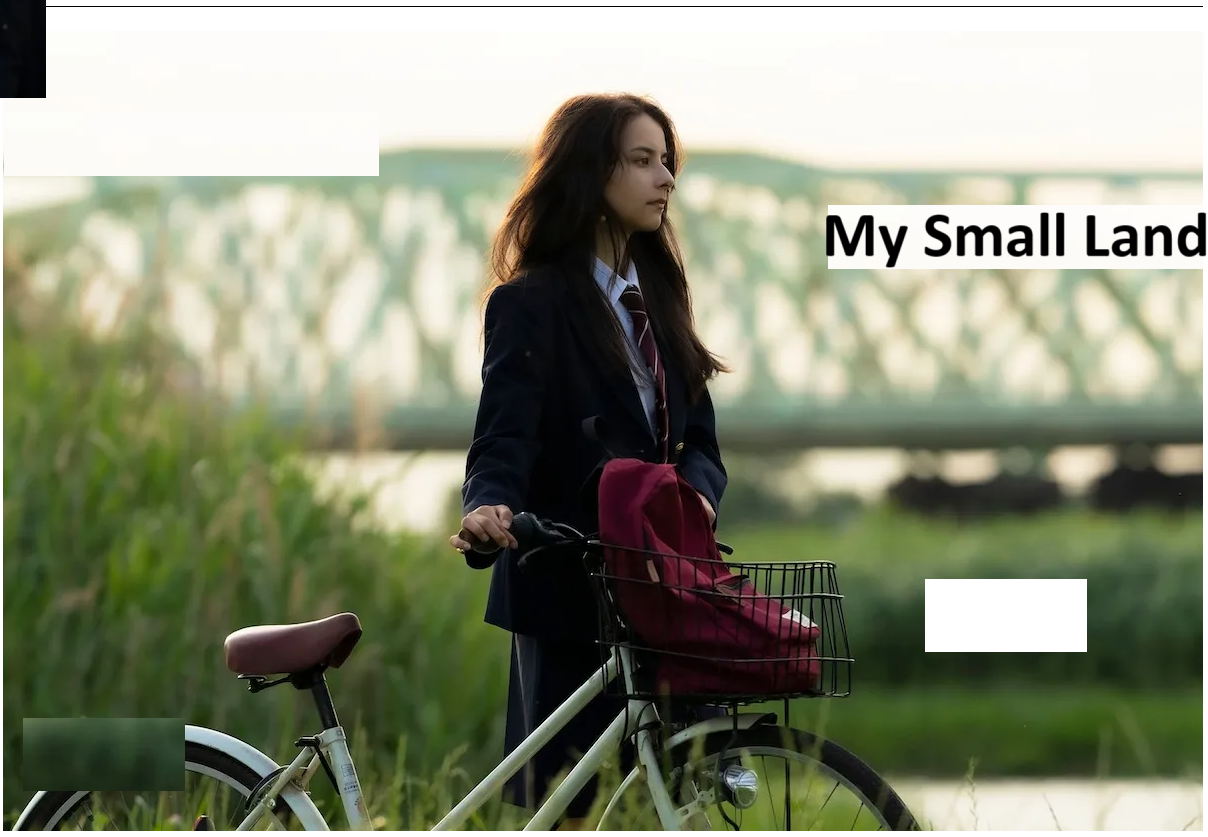

My Small Land

The internet has frequently reported on the tensions between Kurdish refugees residing in large numbers in Kawaguchi City, Saitama Prefecture, and local residents. “My Small Land” portrays the challenges faced by a Kurdish girl living in Japan.

In recent years, citizens have voiced ongoing concerns about deteriorating security conditions, criticizing the media for not accurately reporting the situation. There has been a noticeable increase in hate speech directed towards Kurds. Consequently, there are growing calls for protests against xenophobia and for greater understanding towards Kurdish refugees. The portrayal of the Kurdish refugee issue in the movie “My Small Land” raises important questions about coexistence between foreigners and Japanese residents, which is likely to become even more significant in the future.

Let’s briefly review what kind of people Kurds are.

The Kurds inhabited the territory of the Ottoman Empire from the Middle Ages through the early modern period. After World War I, they were dispersed across Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, following the borders established by France, Britain, and Russia. This geopolitical division left them as the largest ethnic group without a sovereign state, numbering approximately 30 million people.

Kurdish Refugees in Japan from the 1990s onwards

In the latter half of the 20th century, Kurdish communities in Turkey and Iraq faced secession and independence movements. Amid the complex geopolitics of the Middle East, a growing number of Kurdish refugees sought asylum in Europe, fleeing persecution by the Turkish government. Concurrently, starting from the 1990s, a significant number of Kurds began migrating to Kawaguchi City and Warabi City in Saitama Prefecture, Japan. These cities, known for their numerous small and medium-sized industrial enterprises, were welcoming towards foreign workers. Presently, it is estimated that around 2,500 Kurds reside in these areas.

Kurds in Japan: A Review

While many countries recognize Kurds as refugees, the Japanese government generally does not accept applications from Kurds, with only one historical exception. As depicted in the movie “My Small Land,” some Kurds in Japan secure residency by having school-age children or marrying Japanese citizens. However, those lacking such qualifications face severe restrictions—they are unable to work, obtain health insurance, or move freely, often leading to their detention in immigration facilities as illegal overstayers. Others may be granted temporary “provisional release,” but without proper status, they remain vulnerable to losing their qualifications and facing uncertain futures.

The frequent conflicts between Kurds and citizens in Kawaguchi City in recent years can be attributed to the unstable situation of Kurdish refugees in Japan, highlighting significant differences in lifestyle and culture between the two groups.

My Small Land: A work depicting Kurdish refugees living in Japan

This time, we’ll discuss the movie “My Small Land” (2022), which delves into the challenges faced by Kurdish residents in Japan through the lens of a Kurdish girl. The film’s original story, script, and direction were handled by Ema Kawawada, whose background includes a British father and Japanese mother. Drawing from her own experiences of identity, Kawawada portrays a Kurdish girl raised in Japan, shedding light on the intricate circumstances of Kurdish refugees assimilating into Japanese society.

There are no instances of Kurds causing harm to Japanese residents here. However, the film might face criticism for potentially downplaying actual issues. On the contrary, by highlighting the struggles of young Kurds who have grown up in Japan and are striving to build their futures there, the movie provides a perspective that extends beyond mere conflict.

Displayed on the opening screen are three lines of text: “Language of the place you live now/Language of the place you lived in the past/Words passed down by the tribe.” These languages include Japanese, representing their current residence; Turkish, the country they sought refuge in; and Kurdish, the language of the Kurdish people depicted in My Small Land, though not tied to a specific homeland. The roles are clearly defined. Sarya (played by Rina Arashi) is a 17-year-old residing in Kawaguchi City, who arrived in Japan as a child with her parents and siblings. Having lost her mother, she diligently pursues her studies, cherishes her friendships, and dreams of becoming a teacher.

However, as a bilingual in Kurdish and Japanese, she serves as a bridge between the Kurdish and Japanese communities around her, often fulfilling small tasks for them. The Kurdish family, led by their father Mazlum, deeply values their ethnic traditions, evident in the music, elaborate wedding costumes, and traditional Kurdish cuisine enjoyed sitting on the floor. Sarya’s subtle sense of alienation is portrayed with straightforwardness.

Meanwhile, Sarya’s younger sister, Arlin, embodies a distinctly Japanese mentality, while her elementary school-aged brother, Robin, feels isolated at school where only Japanese is spoken. These dynamics within a close-knit family highlight the generational and experiential differences between Japan and Kurdistan. Placing such a family at the heart of the drama, My Small Land portrays the everyday reality of Kurdish life in Japan, shedding light on their unique challenges and cultural richness.

Innocent love and unreasonable fate

To save money for university, Sarya takes on a secret part-time job at a convenience store in Tokyo’s Kita Ward, just across the Shin-Arakawa Ohashi Bridge, without her father’s knowledge. There, she meets Sakiyama Sota (played by Okudaira Daikane), who is also working part-time. As they interact during their shifts, a subtle bond begins to form between them.

The initial conversation between Sota and Sarya is awkward yet innocent, and the natural progression of their relationship slowly closing the gap between them is beautifully depicted. Sota mentions, “I like red,” alluding to the Kurdish red mark that was placed on Sarya’s hand during a Kurdish wedding, a detail she tries to conceal by washing it off, as shown in the film “My Small Land.”

It seems like this is a moment where Sota confesses his feelings to Sarya, saying “I love Tharya.” In response, Sarya reveals her Kurdish identity to Sota, who had previously pretended to be “German” due to societal perceptions in Japan. Sota’s reaction is understanding and compassionate.

After this heartfelt exchange, the scene shifts to the two of them outdoors, where they arrange papers and play with spray paint in different colors. As rain begins to fall, the colors blend together, symbolizing the blending of identities and cultures beyond ethnicities and races. This imagery captures a sense of freedom and mutual understanding between individuals, illustrating a poignant exchange.

Meanwhile, Mazlum, who had been supporting his family through work in the demolition industry, faced the harsh reality of having his refugee application rejected and his residence status not renewed. He was detained at an immigration facility but later released on “provisional release.” Under these conditions, Mazlum is unable to work, lacks an insurance card, and is restricted from traveling outside the prefecture. This situation reflects the challenging circumstances faced by many Kurdish refugees living in Japan.

However, if Mazlum returns to Turkey, he faces a high risk of detention due to his past involvement in the independence struggle. The heartwarming love between Sarya and Sota, who had dreams of attending art school together in Osaka, abruptly takes a tragic turn due to their family’s crisis. Sota becomes frustrated with the unjust fate of Kurdish refugees he had never fully understood, yet he realizes there is little he can do to change their circumstances.

During this period, a sudden incident exposes the disconnect between Mazlum, who deeply values Kurdish culture and traditions as depicted in “My Small Land,” and Sarya, who struggles to find meaning in them.

Furthermore, Mazlum was apprehended while working and was forcibly placed in an immigration detention facility. Amidst the anxiety and turmoil of losing their primary breadwinner, the family’s emotions quickly unravel. Providing support to this struggling family are Sota, who comes from a single-parent household, and his mother. In a poignant scene at Sota’s home, Sota, his mother, Sarya, and Robin gather around a modest dinner table, portraying a semblance of a happy surrogate family. However, after losing her job at the convenience store, Sarya feels compelled to distance herself from Sota while trying to maintain a sense of pride.

Navigating challenges that are exceedingly difficult for a 17-year-old, Sarya’s graceful countenance reveals a poignant blend of profound sadness, helplessness, and an unwavering resolve to shield her beloved from these hardships.

The role of reconnecting families

The scene where she walks across the Shin-Arakawa Bridge on foot, her bicycle hidden by her father, symbolizes the challenges experienced by Kurdish residents in Japan, as depicted in My Small Land. The red handprint that Sota and she had once placed on the prefectural border at the center of this bridge has been erased, replaced by a “no graffiti” sign. It serves as a stark symbol that even small acts of resistance against division can be swiftly suppressed by national laws.

Threatened with eviction by his landlord due to unpaid rent, Sarya uses the money he saved from his part-time job for university living expenses. Despite borrowing additional funds from Kurdish acquaintances, it proves insufficient. A friend suggests that Mazlum take on work as a day laborer to alleviate the financial strain. Even Sota’s earnest attempts to assist fail to resonate deeply with her emotional turmoil. For a more detailed understanding, I recommend watching the movie “My Small Land” for a visual and comprehensive depiction of these events.

In this scenario, Robin, the youngest member of the family, assumes the role of bridging the gap between the estranged family members. His father’s poignant statement, “These stones, whether Kurdish or otherwise, nothing will change,” resonates deeply with Robin, who connects this sentiment with the free drawing technique Sota taught him. Through his artistic expression, Robin blossoms amidst his solitude, silently illuminating a ray of hope within the familial turmoil. This poignant scene, where the most vulnerable character in the narrative communicates profound optimism through his own creativity, evokes parallels with the conclusion of “Tokyo Sonata” (directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2008).

The tale of an olive tree in his homeland, narrated by Mazlum, illustrates a profound decision made for the future of his children. In the garden, an olive tree nurtured first by Mazlum’s father, then by Tharya, and now by Robin, stands as a poignant symbol. It signifies the enduring bond between a father and son separated by the circumstances of their respective countries, suggesting they may never reunite. Despite the physical distance, the two olives, thriving in distant lands, serve as a poignant reminder of their shared heritage and Mazlum’s enduring legacy.

The remaining children in the household are now reliant on the kindness of non-family members with limited means. Despite the unimproved circumstances, Tharya’s gaze reflects a resolute determination to forge her own path in Japan, the land where she was raised, a testament to her unwavering strength.

Must Read: FINLAND THE HAPPIEST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD 5 REASONS TO VISIT